Readings

(click the header to view the readings)

Isaiah 4:2-6

1 Thessalonians 4:13-18

Luke 21:5-19

Reflection

Observing Advent is harder than observing Lent. Lent is the more penitential of the two seasons, but the readings are so familiar that it is easy to gloss over them. We know the challenges of Lent all too well, and we sometimes observe it by turning it into a self-improvement project as we valorously giving up our vices. Lent can actually feel good and familiar to those who observe it regularly. We can shape it so that it doesn’t chafe or challenge us too much.

Advent is different. It is decidedly counter-cultural, both in terms of what the broader culture is doing, and in terms of its themes. While the culture-at-large is engaged in a holiday frenzy, Advent asks us to slow down, to watch and wait. While the culture-at-large seeks to defer and deny aging and death, Advent asks us to be painfully aware that an end will come.

I’m finding writing about the daily readings of Advent to be a challenge. Advent’s readings are disturbing—even infuriating—to our modern minds. They are rife with judgement and destruction, and if we are honest, the God they portray can seem like an abusive tyrant. In this regard, it is helpful to recall that the Advent readings were written across a period of time where violence was regularly and ruthlessly deployed by political leaders. Violence was also often the answer to broken promises between parties. The prophets and apostles were creatures of these times, and the language they used to communicate with those to whom they were writing is burdened by this perspective. So we have to look more deeply. I want to describe the process and lens (hermeneutic in theology-speak) that I will use to do this deep looking for the remainder of Advent.

The process involves three steps: articulating the concern of the reading, understanding what it requests of us, and searching for hope. This process can lead us beyond the violence and tyranny in the readings into something deeper they may be offering.

The lens through which I will search for hope is the hermeneutic of interbeing. Interbeing is the insight that everything in the created order is empty of a permanent, separate self. Everything changes, and each entity depends on and arises from all of the other entities in the universe. Consider a loaf of bread. We know that the bread is impermanent, that if we leave it on the counter it will eventually mold and come apart. What we don’t usually realize is that the bread is dependent on everything else in the cosmos for its existence. We know that wheat requires a seed, soil, water, and light. But each of these conditions for wheat has other conditions on which they depend. The seed requires earlier wheat, the soil requires ongoing replenishment from the decay of plant and animal matter, water comes from rivers, streams, or rain, and the light comes from the sun. Going further back, the once-living matter that becomes the soil requires molecules and atoms that constitute that matter. Water requires hydrogen and oxygen. And the sun is a huge ball of super-dense hydrogen. All of the atoms for living matter, water, and the sun arose in the first generation of stars after the Big Bang, and were scattered across the cosmos as those stars died. If we follow the chain of necessary constituents for the bread, we won’t find a few linear list of links of things that precede the bread. Instead, we discover a web of interconnection that includes everything in the entire cosmos.

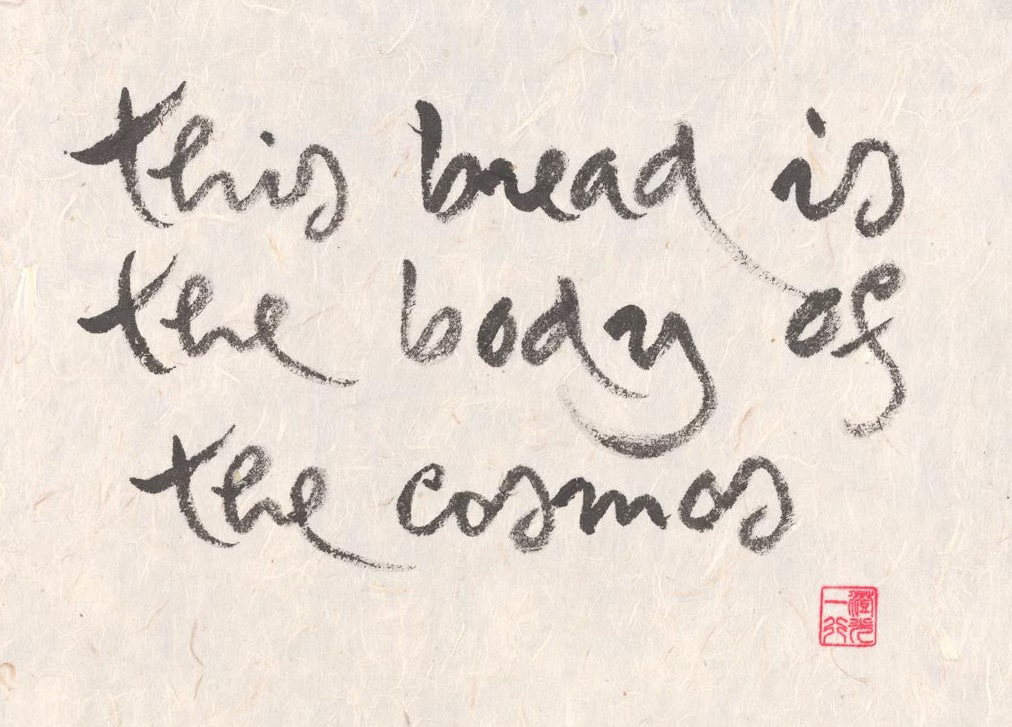

Thich Nhat Hanh coined the term “interbeing” to describe this radical interdependence. Everything “inter-is.” In one of his beautiful pieces of calligraphy, Nhat Hanh writes that the piece of bread in our hand is the body of the cosmos. This is interbeing, and everything in creation has this nature.

Moreover, because everything “inter-is,” those things that we consider opposites (right/left, right/wrong, etc) are actually interdependent. They always exist together, and you cannot have one of them in isolation. Consider right and left. Suppose you have a stick that is two feet long, and you decide to remove the left part of the stick so that only the right part remains. Cutting off one foot from the left end will not leave a stick that only has a right end. You will have two sticks, each one a foot long, and each with a left and right end. Right and left are interdependent and cannot exist in isolation. The same is true of good and evil, suffering and compassion, and all other opposing concepts. This is a deep and possibly unsatisfying teaching for many Christians, but if we take our experience seriously, we will see that there is truth in it. Our Buddhist friends would tell us to look even deeper, because it is not only true, but it is good news. Over the remainder of Advent, I hope to explore this good news more deeply, using our readings as a basis for this exploration.

Starting tomorrow, I will usually reflect on the readings using this threefold process and lens. I hope this will lead to reflections that are more nourishing for you to read, and easier for me to write. Stay tuned!

Prayer

God our weaver, you knit all of creation together in interbeing, that great, dynamic web of belonging in which everything exists. Give us grace to see and deeply understand our interdependence, and guide us to care for all that is as our own true body. Amen.