This is part 2 of an exploration of how Trump won the 2024 election and what we do about it. This essay will look at how we care for ourselves in the post-election world. Part 3 will look at how we heal the culture to reduce the harm his return is bringing.

Like many changes, healing our culture from the anger, greed, and delusion that led to the return of Trump is straightforward to describe, but difficult to enact. As individuals and as a society, we must cease to consume the nutriments that lead to our afflictive and deluded mental states. In Buddhist terms, we are seeking to nourish ourselves in such as way that allows us to clear the dust from the mirror of the mind, ensuring we apprehend and reflect what is true and real with wisdom, courage, and compassion. In Christian terms, we are seeking to put on the “Mind of Christ,” abiding in loving communion with the source of life and with one another.

We must no longer be children, tossed to and fro and blown about by every wind of doctrine, by people's trickery, by their craftiness in deceitful scheming. But speaking the truth in love, we must grow up in every way into him who is the head, into Christ, from whom the whole body, joined and knit together by every ligament with which it is equipped, as each part is working properly, promotes the body's growth in building itself up in love.

— Ephesians 4: 14-16

Our aim is to realize basic goodness and restore sanity to ourselves and our society.1 Our practice is to first tend to our own mental state, as we must be solid and free to skillfully engage others in our divided and divisive times.

A parable offers some insight into why we must tend our own minds first. Our shared life can be compared to a building. It is a structure with many and varied rooms in which different communities of people abide. These represent the different views of society. Although there are different rooms, we are all charged with tending this structure.

Suppose the structure catches fire. This represents the state arising when anger, greed, and delusion begin to erode and devour our society. Outside of the structure there are buckets of liquid representing the actions we can take to address the fire. Some of these buckets are filled with water, and others with gasoline, representing the reality that some actions we take in response to the afflictions of society will calm the situation, and others will inflame it. To properly tend our structure, we must have the insight to tell which buckets we should grab and throw on the fire. Our first priority must be the development of this insight.

Let us take the analogy a step further. A frequent delusion is the aggresive belief that we must eliminate, dominate, or destroy those with whom we disagree. This is the equivalent of believing that we will save our structure by throwing gasoline buckets on the parts of the structure where we find those with whom we disagree. The reality is that the fire will still be fed, and the whole structure will be in peril. The viewpoint of aggression must be transformed before we can act in ways that will truly save our society, and the transformation of aggression is an internal process.

Tending Our Minds

The process of internal change requires that we develop a commitment to the cultivation of our own consciousness in order to reduce (and perhaps someday remove) the afflictions of anger, greed, and delusion. This commitment manifests via our willingness to develop and practice contemplative skills that help us to realize three aims.2

To gain the bravery to really get to know ourselves.

To discover a basic goodness that undergirds human existence.

To develop a genuine and tender relationship to all that is.

The basis for realizing these aims is the practice of sitting meditation or contemplation. At the conclusion of this article, I will provide some resources for people who are interested in committing to a meditation practice. By committing to and engaging in a contemplative practice, we slowly begin to excavate the claustrophobic bind in which most of us live.

The Cocoon of Shyness and Aggression

Chogyam Trungpa likens the claustrophobic bind in which we live to a cocoon, spun from the relentless chatter of our minds and the actions that this chatter encourages. We are imprisoned in this cocoon, yet we are unaware of both our loss of freedom and of behaving in ways that sustain the cocoon. The cocoon is a narrow, stale, and airless place, but we are so used to its confines that it becomes almost invisible to us, and we grow comfortable abiding in this self-generated prison.

Two strong energies weave the cocoon: shyness and aggression. To moderns ears, these seem very dissimilar, but they are deeply related. Shyness describes the inner critique and resentments we have that keep us from true knowledge of who we really are. Spinning in shyness, our thoughts create and then critique an imagined self, precluding a true relationship ourselves as we really are. Aggression is the outer critique, the constant judging, comparing, and complaining that keeps us from an intimate encounter with other beings and things as they really are. In both cases, the thread of judging thoughts and words winds around us again and again, weaving the stale, dark cocoon that we mistake for safety.

Opening the Cocoon

Even as we are bound tight in our cocoons of shyness and aggression, something (I believe it is grace) creates a longing for openness. This usually arrives via some sort of experience of “hitting bottom.” Something causes us to understand just how confined and trapped we are, how stale and dead we are as we live within the cocoon. We understand that the energies of shyness and aggression have not served us well or made us safe. Rather, they have made our lives intolerable.

Seeing this is a good thing! It provides the impetus for us to act, to stop weaving the cocoon, and to seek to encounter ourselves and our world as they really are. We realize this impetus when we have the courage to stop running, calm our minds, rest in reality, and heal our afflictions. These four actions—stopping, calming, resting, and healing—are the foundation of meditation.3

Yet meditation remains deeply misunderstood in our culture. Many people believe that it is a way to “bliss out” and acquire peace. This is incorrect — meditation has nothing to do with acquisition of anything. Meditation’s concern is realization of reality, and this includes the reality of who we are, of what is really real, and from where we have come.

Including all of reality means that the cocoon itself is an object of our meditation. Trungpa states, “We have to develop genuine sympathy for our own experiences of darkness as well as those of others.”4 Even as we step from the cocoon into a brighter, fresher world, we stay aware of the closed and dank place from which we escaped, and we feel genuine sympathy for ourselves and for all who still struggle with the cocoon. And our past cocoon experiences (and the inevitable occasional returns to it that we make) are not the only challenging experiences in our lives that become part of our meditation. We commit to encountering ourselves “just as we are” on the cushion. The true definition of bravery is to not be afraid of who we are, and we simultaneously develop this courage and get to know ourselves in the stillness and silence we accept when we sit down to meditate.

Discovering Basic Goodness

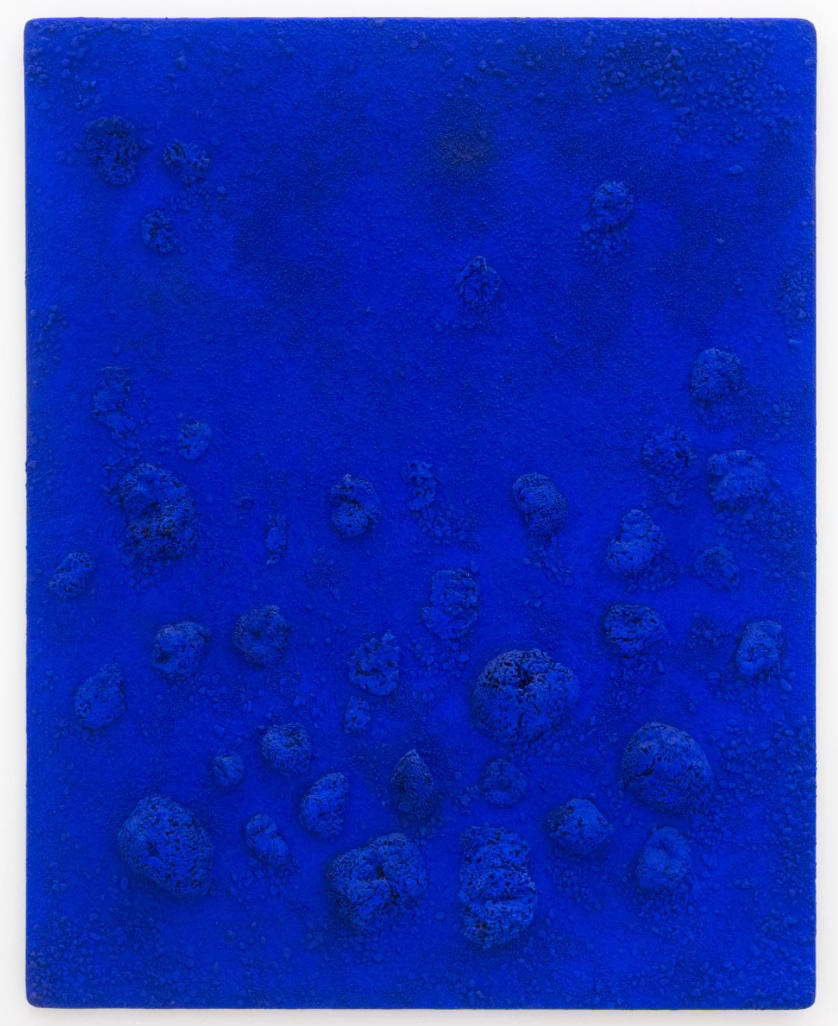

Over time, our commitment to contemplative practice will begin to infuse our lives with mindfulness, and we may discover a basic, fundamental goodness to our existence. This isn’t goodness in a moral sense, but something much more foundational. The facts that we can smell cinnamon baking, see the electric blue in an Yves Klein painting (Figure 1), or feel the caress of a loved one all point to something fundamentally good about our existence.

This goodness is not acquired, but realized. It cannot be lost, but it can be ignored or forgotten. When we are in touch with this goodness, our lives take on depth and meaning, and we begin to care deeply about all beings and about our world. We see our world from the vantage of the rising sun, growing brighter and illuminating the glory and beauty of the gift of creation. When we turn away from the cocoon and live fully into this basic goodness, we arrive in the Kingdom of God right here and now. This is the true meaning of repentance.

The time is fulfilled, and the kingdom of God has come near; repent, and believe in the good news. — Mark 1:15 (NRSV)

Creating Genuine Connection

Having come to know and accept ourselves—including our shadow and struggles—and seeing that basic goodness is inherent in existence, we are liberated to develop genuine and tender relationships with others. Because we have encountered, accepted, and transformed at least some of our own suffering and darkness, when we encounter darkness and suffering in others, we no longer need to defend against, control, or dominate them. Even as we work to prevent or reduce the harm that they may be causing, we do not work against their being.

Having developed the courage to encounter ourselves, we find that it now extends to getting to know others and to loving them. We even become able to love our enemies and pray for those who persecute us (Matthew 5:44). At this point, our stability is solid, and we have the insight and compassion required to engage in even the most challenging circumstances, provided that we continue and maintain the practice of contemplation.

A Reminder about Nutriments

It is important to remember that meditation doesn’t only occur when one is seated. We should aim to live mindfully at all times, fully aware of where we are and what we are doing. We must also practice a “diet” by only ingesting nutriments that encourage love and compassion to arise in our hearts. For a reminder on how we can do this, please see these essays:

Seeds of Joy - an introduction to Buddhist psychology

Feeding the Seeds - an essay on mental nutriments and Buddhist psychology

Selective Touching - an essay on managing our mental states

Conclusion

In part one of this three part series, we explored the role of toxic nutriments in Trump winning the 2024 election. In this essay (part two), we explored the fundamental nutriment of meditation and the effects it offers, including helping us know ourselves, showing us basic goodness, and helping us to have genuine, tender relationships with all beings.

The third and concluding essay in this series will address how we engage to reduce the harm that the Trump administration is causing.

Learning to Meditate

Here are a few resources to those interested in learning how to meditate. First, I am part of an interfaith community called Living Christ Sangha that meets every Sunday on Zoom from 3:00-4:30 PM ET to meditate together. You can learn more about us by visiting our website at https://www.livingchristsangha.org.

If you are interested in practice from the Buddhist tradition, there are two excellent books by Thich Nhat Hanh that discuss foundational practice.

Breathe! You are Alive! This is a translation and commentary on the Anapanasati Sutta (sutra), which explores mindful breathing as the basis for meditation.

Transformation and Healing. This is a translation and commentary on the Satipatthana Sutta (sutra), which explores mindfulness of the body, feelings, thoughts, and objects of thought as a basis for continuous meditation.

If you are interested in the Christian meditative tradition, I recommend these two books.

Gratefulness: The Heart of Prayer by Brother David Steindl-Rast. This gem of a book explores the practice of gratefulness as both a source of deep prayer and as a way to live wholeheartedly in the present moment.

Into the Silent Land by Martin Laird. A book about the practice of Christian contemplation. It is both crystal clear and very mystical at the same time.

This is the purpose of our practice that Tibetan teacher Chogyam Trungpa describes in his book Shambhala: The Sacred Path of the Warrior. Many of the concepts presented in this essay are based on the Shambhala path.

Trungpa, Shambhala, pp. 23-46.

In chapter 6 of The Heart of the Buddha’s Teaching, Thich Nhat Hanh says “We have to learn the art of stopping — stopping our thinking, our habit energies, our forgetfulness, the strong emotions that rule us.”

Trungpa, Shambhala, p. 62.